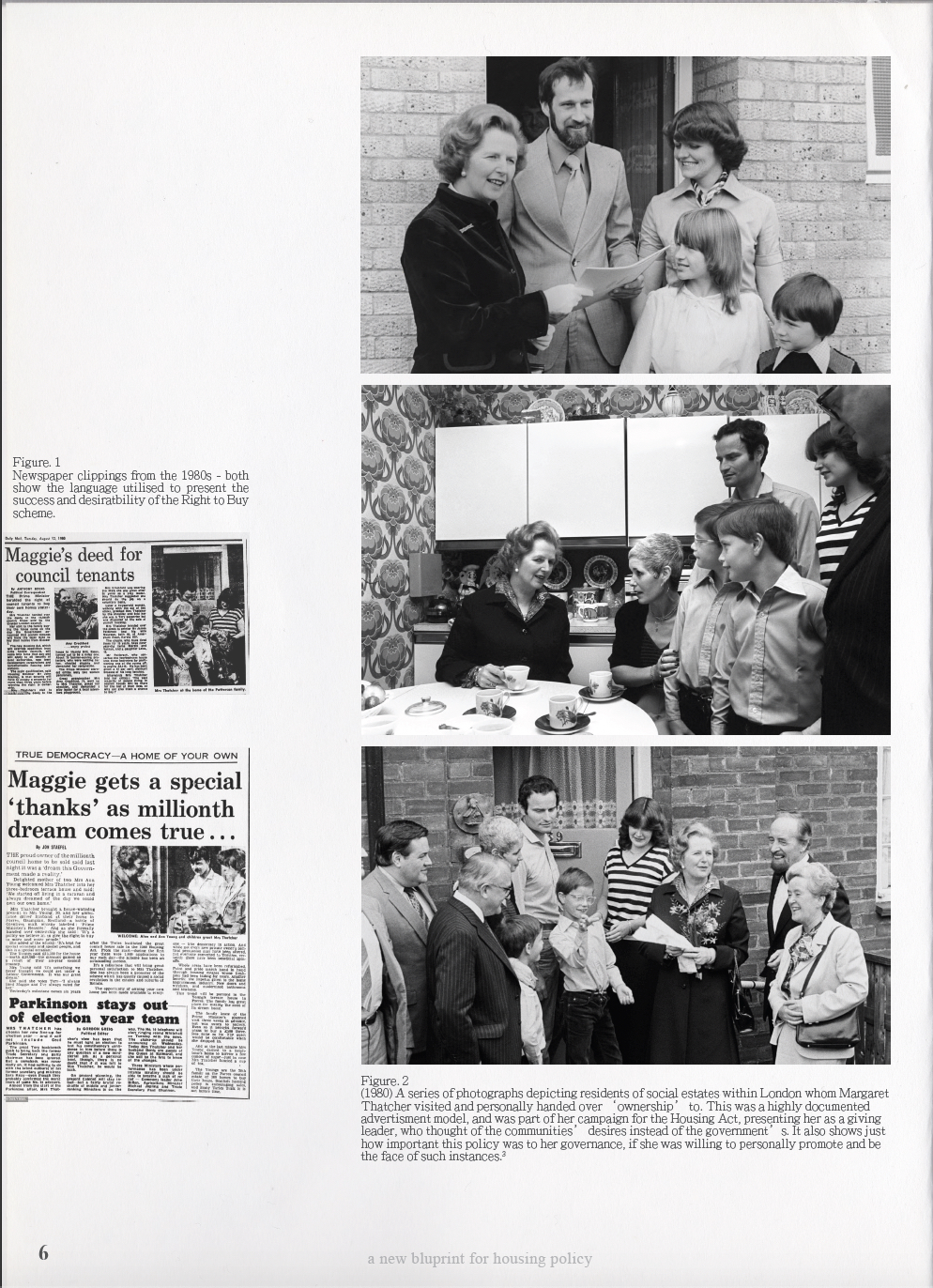

Homeownership has long stood as the cornerstone of British housing policy, heralded as both a personal aspiration and a route to social mobility. Rooted in 19th-century ideals and cemented by Thatcher’s transformative Right to Buy scheme, this model has shaped not only policy but the national imagination. Yet in contemporary London—marked by transience, economic precarity, and demographic complexity—this vision of stable, property-based domesticity is increasingly disconnected from lived realities. Through the lens of the 2020 Social Housing White Paper, this essay critiques the policy’s nostalgic attachment to ownership and questions its relevance in a shifting urban landscape.

Rather than breaking from the past, the White Paper reinscribes ownership as an unquestioned good, cloaking familiar ideologies in the language of tenant rights and reform. By tracing the historical rise of ownership through legislative shifts, media narratives, and cultural symbols, the argument reveals how property came to represent moral virtue, familial success, and upward mobility. Yet today, in a city dominated by short-term tenancies, shared housing, and structural exclusion, the promises once attached to ownership have grown hollow—more aspirational than attainable.

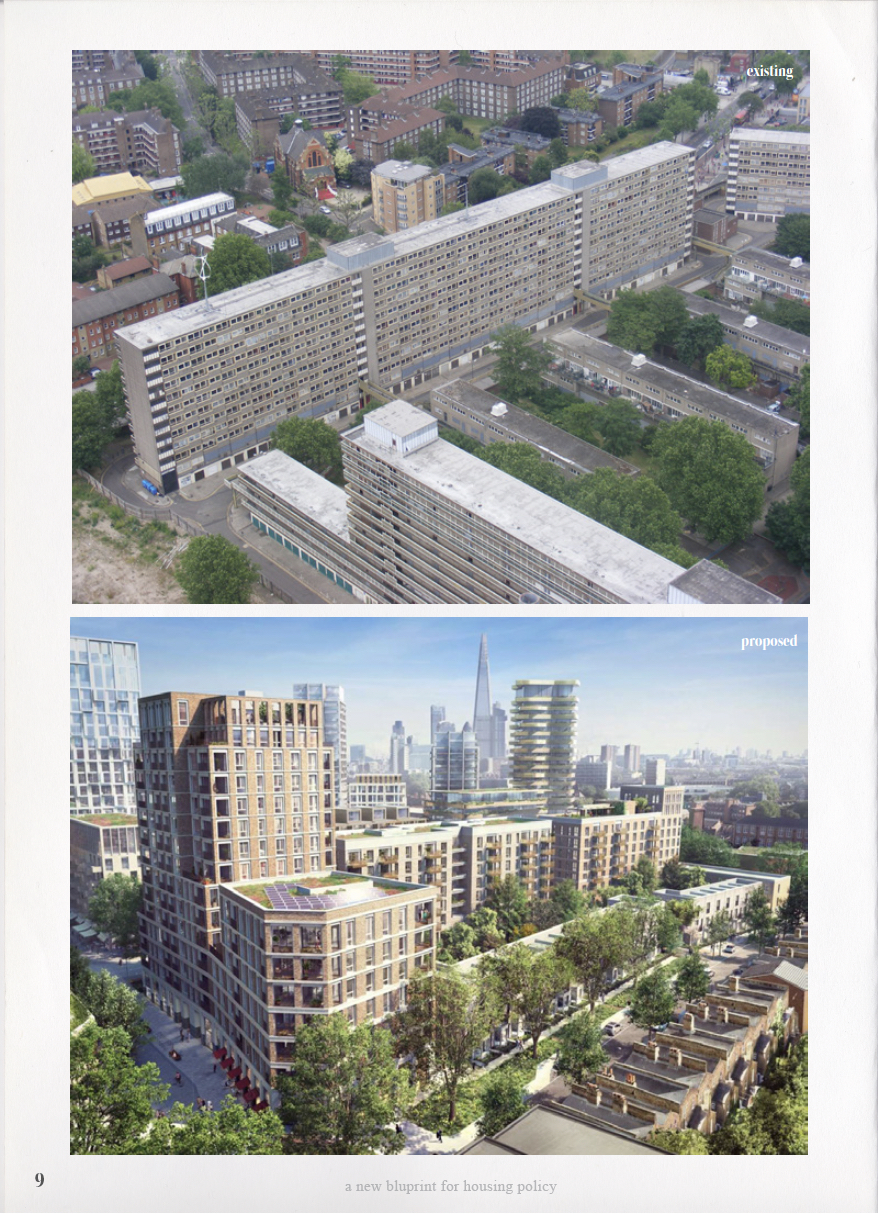

As developments like the Heygate Estate demonstrate, policies built around ownership have accelerated displacement, not access. Housing in London has become less a place of belonging than a vehicle for capital. The essay asks whether ownership, as a housing model, can adapt to contemporary conditions—or whether it is time to abandon it altogether. Rather than modernise a fading ideal, the future of housing may lie in reimagining it as collective infrastructure: adaptable, equitable, and reflective of the plural, precarious realities of urban life.

|